Economies of scale: a proportionate saving in costs gained by an increased volume of production.

The reason Tesla names its Nevada battery production factory the Gigafactory was to help people understand that only when operating at a larger economy of scale does EV battery production truly become profitable.

Tesla’s mission is “to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.” Now, I don’t want to predict whether Tesla will have to do all of the heavy lifting to completely transition the earth to sustainable energy or if it only needs to get the ball rolling and make the blueprints. My goal is simply to help people understand where we are now and what it is going to take to move the world to sustainable clean energy through battery power. The real world is much more complex, but this simplified math should give a good general image of the situation.

Battery Uses

First off, let me start by explaining that there are 4 main uses for batteries.

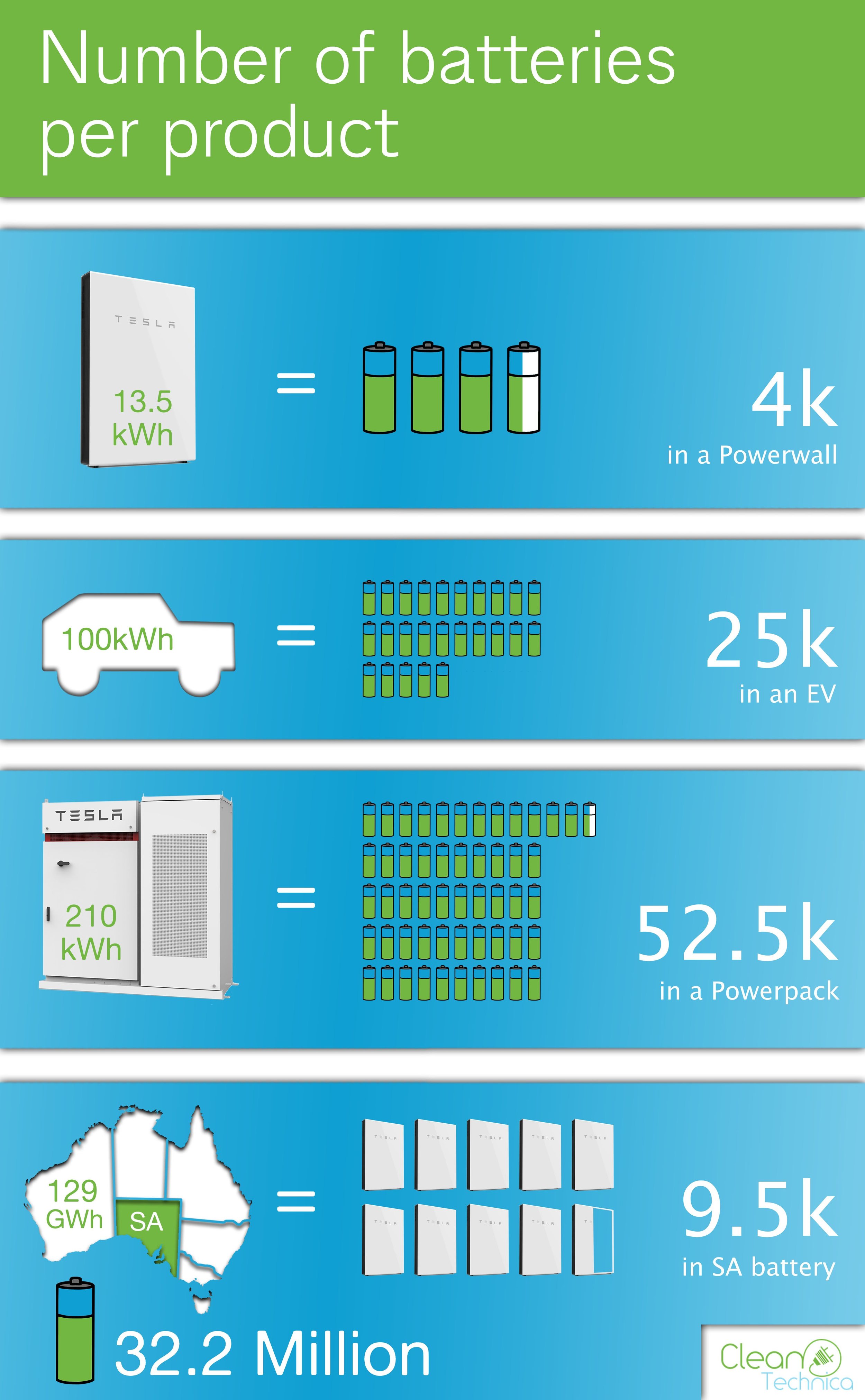

Up until recently, the most common uses for batteries were all kinds of consumer electronics. A single AA battery has an energy capacity of approximately 3.75 watt-hours. But for the sake of round numbers, let’s say that a single AA battery has 4 Wh or 0.004 kWh of capacity.

The second most common use for batteries is electric vehicles. EV batteries come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from 16 kWh all the way to 100 kWh. As a couple of examples, a Volkswagen e-up! has about 18.7 kWh of battery capacity and a Tesla P100D has 100 kWh.

The size of a home battery storage unit ranges from 2 kWh to 17.1 kWh per unit. According to Tesla, most households need or will need about 27 kWh, which is why its 13.5 kWh Powerwalls are sold starting with 2 units.

The last and newest battery usage that recently became popular is industrial/utility-scale battery storage. The Tesla Powerpack has a capacity of 210 kWh per Powerpack. The current largest battery installation in the world is in South Australia. It has 129,000 kWh, which is about 614 Powerpacks.

Some Fun with Statistics

According to one statistic, in 2017, there were almost 71 million passenger cars sold worldwide. Now, let’s assume all of the following to be true:

All 71 million cars are electric.

Every car has a 70 kWh battery pack (this is average for cars with what is now considered an adequate range).

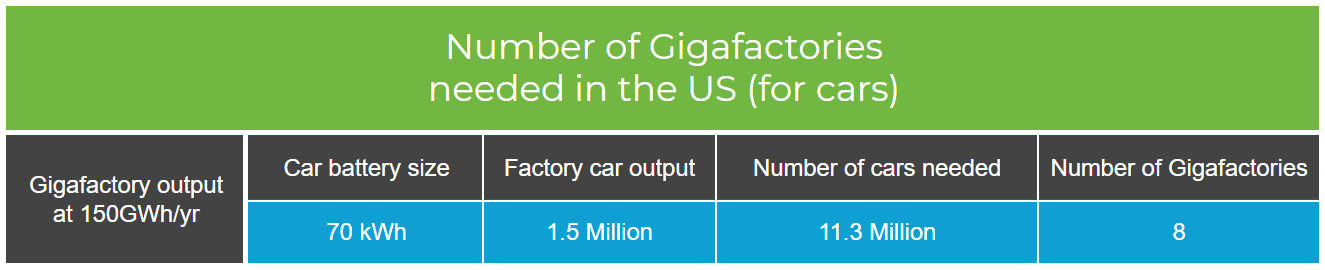

The Tesla Gigafactory 1 is the largest battery factory in the world. As of the end of July 2018, the Gigafactory had a production rate equivalent to ~20 GWh/yr. By the end of 2018, Tesla planned to be at a production run rate of 35 GWh per year. Once the construction of the Gigafactory is complete, it is supposed to have a total capacity of 105 GWh of battery cells and 150 GWh of total battery pack output per year (which includes EV batteries, Powerwalls, and Powerpacks).

Now, obviously, this has been oversimplified. Passenger cars are not the only vehicles on the roads. Nonetheless, if you wanted to meet the world’s 2018 demand for cars purely with EVs, with every Gigafactory not producing any Powerwalls or any other products, you would need 34 factories that are almost 8 times larger than the largest battery factory in existence today. In other words, if you build the factories the size that the current Gigafactory is today, you would need 249 of them.

A lot of people currently believe that the worldwide battery shortage will be met within the next 2 years. That is beyond ludicrous. To meet the worldwide battery demand for EVs alone, we need a chain of Terafactories, not Gigafactories.

Powerwalls & EVs in the United States

Unfortunately, there is very little information on housing and electricity usage per household per country across the world. Thus, it’s extremely difficult to calculate how many Gigafactories we would need to supply the entire world with Powerwalls. (There are also numerous other factors that must be considered to determine how many home storage batteries are needed.) So, instead, let’s try to calculate how many Gigafactories we would need to provide the entire United States with Powerwalls so that, in combination with solar or wind, all households could become self-sufficient. (There are reasons why this is not the logical solution — not every home needs to be equipped with an energy storage unit, and handling storage on the utility scale is largely more efficient. But it seems useful to include in this thought + math experiment.)

There are 126 million households in the US. On average, most households need at least 2 Powerwalls. One Powerwall has a usable capacity of 13.5 kWh. However, in reality, the battery probably has at least 15 kWh. This is to make sure that you can’t charge it to the maximum and always have a minimum reserve. This way the battery will have a longer lifespan. So, in total, we need two 15 kWh Powerwalls (30 kWh per household). That is a total of 3,780 GWh for the entire United States. Let’s assume that a Powerwall needs to be replaced every 10 to 30 years depending on how you use it. Let’s calculate how many Gigafactories we need in order to manufacture 3,780 GWh of energy storage every 10, 20, or 30 years.

We know that Gigafactory 1 will devote 45 GWh to Powerwalls and Powerpacks and 105 GWh to battery packs for cars, so let’s make 2 separate calculations for the potential 10, 20, or 30 year product lifespan.

Now, let’s redo the previous calculation about cars but only for the United States. In 2017, there were 71 million cars sold worldwide, and there were 11.3 million sold in the United States. That means we need 791 GWh.

Now, if energy and car demands don’t rise from 2017 levels and if Powerwalls last at least a little over 10 years, then 8 Gigafactories should be enough to cover all passenger car and residential Powerwalls needed in the United States.

In Conclusion

At this point, I feel inclined to point out that I don’t care how quickly the Chinese, the Germans, Tesla, or anyone else can build large factories — they are not in competition as much as they are in cooperation on the macro scale. There is a shortage of lithium-ion batteries and there is absolutely no way that we can build enough batteries for our needs quickly, not in the next 2 years, not in the next 20 years.

We are going to need much larger and more favorable economies of scale and a cost per kWh that is a lot lower than the $100 per kWh world record that Tesla has just achieved. In addition to that, factories need to become even more space efficient. Tesla’s improvement from 35 GWh to 150 GWh is a notable achievement in that direction, but even they can and will do better eventually. I just hope that other brands will learn from them.

We are not going to need Gigafactories, we are going to need Terafactories or even Petafactories that are built everywhere around the world and not just by Tesla — by everyone. This is the only way that we will be able to meet the constantly increasing global demand for batteries. Companies should be on their knees begging Tesla for its technology and Gigafactory blueprints if they want to stay relevant in the industry.

Stay tuned for part 2, where we will look at past, current, and planned battery factories — what products they produce and for whom.

Read more HERE